Today, we are experiencing waves of regulation and re-regulation of gambling throughout the world. In the U.S., the Supreme Court decision overturning the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, finding that PASPA violates the states’ Tenth Amendment rights, cleared the way for states to determine whether to legalise sports betting within their borders. The Biden win makes it unlikely that the DOJ will appeal the First Circuit Court’s decision that narrowed the application of the Wire Act. These two decisions have meant that states are willing to contemplate legalising and regulating online betting and gaming. It is now inevitable that more states will choose to follow suit and legalise, initially, sports betting and eventually, casino games too.

Contrast this with Europe, where we have had legal online gambling since the early noughties and over on this side of the Atlantic, there is a belief amongst politicians, the media and regulators that gambling is too available and needs to be reined in.

Some countries are restricting the location of gambling arcades, to such an extent that many will close. Other countries, especially in Middle Europe, have given the right to the local municipalities to decide whether they want any gambling within their borders, leading to the closure of casinos and arcades in Bratislava, Prague and Riga, to name a few of the larger cities. Italy has reduced the number of gambling machines and, along with the UK and Spain, are restricting the advertising of online gambling. All of this in the aim of reducing the harms from gambling.

Perhaps the most contentious of all of the ideas to reduce gambling harm is that proposed in Great Britain: to impose a default deposit limit with some kind of affordability check if people want to gamble above the default level. I find it a mind-boggling incursion into our personal freedoms that the Government would limit the amount that someone can spend on a legal activity.

We may think that limiting gambling, restricted advertising and affordability checks are new ideas, but they are not. Attitudes toward gambling have waxed and waned throughout the centuries. The late Professor Bill Eadington posited that throughout history, organised gambling was allowed to expand until there was some kind of scandal involving gambling, after which it was restricted

General attitudes to gambling have not always been opposed. The Old Testament makes a few mentions of gambling. Samson makes a bet with his groomsmen, which he loses, and an Assyrian officer bets King Ezekias of Judah two thousand horses, “if you are able on your part to set riders on them”. In Greek myth Poseidon, Zeus and Hades play dice to decide how to divide the world and Mercury plays a dice game with the moon and wins a portion of her light. All with no mention of gambling being wrong.

In Roman times, gambling was not seen as a vice, nor something to be avoided. The Roman historian Setonius wrote that Emperor Augustus was not upset when people called him a gambler, as he openly played dice games. Emperor Nero “would stake 4,000 gold pieces on each pip of the winning throw at dice”, though he doesn’t write what happened to the winners if Nero lost.

Some did disapprove of gambling. Seneca, for example, ridiculed Emperor Claudius for his “gambling habit”. He envisaged Claudius being sent to Hades, condemned to picking up dice forever, putting them in a box without a bottom.

In the Roman Empire by 204 BC, gambling was prohibited by law except on chariot racing and sports that involved bravery. In 81 BC, a law was passed to protect gamblers from unscrupulous players; creditors could not sue for gambling losses, but losers could sue the winners for the losses they had incurred. There is some discussion amongst historians that this was to protect people who were sometimes forced to gamble against their will, rather than to discourage gambling itself.

Late in the third century AD, the early Christians came out against gambling. St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, wrote a sermon on the evils of gambling (it is now believed this might have been mis-ascribed to St. Cyprian). The sermon, ad aleatoribus (to gamblers), is quite incendiary, full of fire and brimstone, and dice are described as the “snare of the devil”. He writes, “I tell you it is at the gambling table where insane frenzy and dishonest transactions transpire, and where language is as poisonous as a serpent’s venom”. You get the gist. Gambling was not his favourite activity.

The third Crusade at the end of the 12th century saw possibly the first introduction of crude affordability checks. Participants in the Crusade received detailed instructions on how to behave, which included the extent to which they could gamble. Nobody below the rank of knight was allowed to play for money. Knights and, interestingly, the clergy were allowed, but were forbidden to lose more than 20 shillings per day. It was acceptable behaviour to rape, pillage and plunder, but not to lose more than 20 shillings in a day.

In 1255, Louis IX forbid both the playing of games with dice and their manufacture. This was not to stop people from gambling, but from spending time playing games. Indeed, in the latter part of the Middle Ages, not only gambling with dice was frowned upon, but also games such as chess and backgammon. Both games were played in the Middle Ages (and later) with bets made by participants and spectators.

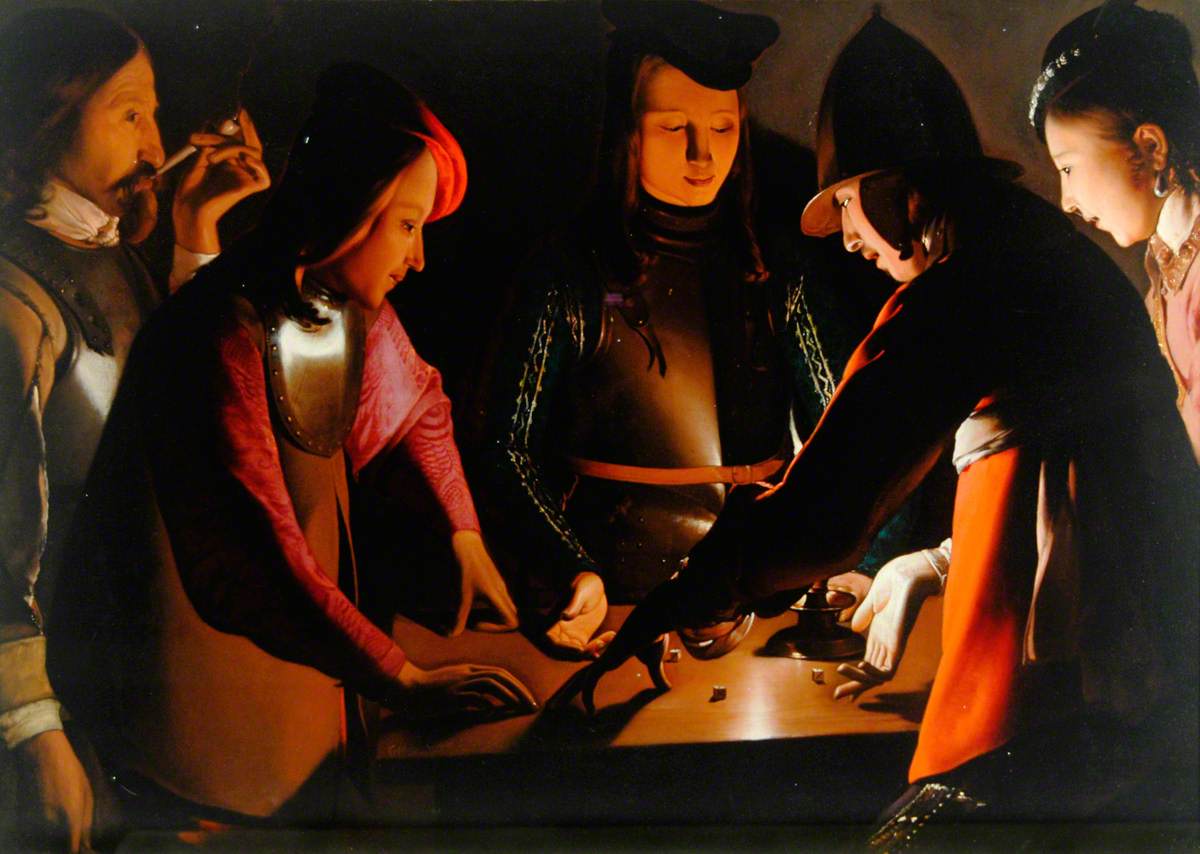

During these times, the objections to gambling, including those from the Church and others, was not that it made people greedy or could quickly part people from their money or goods, but that it encouraged idleness. Also, the hostility was directed at what went on around, rather than on, the gambling tables: foul language, drunkenness, debauchery and fornication. In Chaucer’s “The Pardoner’s Tale,” one of his Canterbury Tales, he writes of the blaspheming that goes on during a game of Hazard, a precursor to modern-day craps. Some disapproved because gambling encouraged disloyalty and deception, and a few did not like that gambling creates “too much excitement”.

Edward III (1312–1377) prohibited certain games in order to promote “manly sports”. Henry VIII (1491–1547) created a list of unlawful games that included dice and cards, although the law did not apply to him. In the immortal words of Mel Brooks, “It’s good to be the King!” Henry’s list also included bowls and hockey; it was not that he had a moral objection to gambling, but that playing these games meant that participants were not practising their archery or sword skills. In Henry’s time, there was no standing army, so he wanted his citizens to be skilled fighters, rather than adept game players, when it came time to wage war.

In France, King Louis XIII (1589–1610) was passionate about gambling and encouraged it in the environs of his royal home. The Palais Royal became a focal point for gambling in Paris; baccarat was introduced here sometime in the late 17th century. By the time Napoleon I (1804–1814) became Emperor, the Palais Royal had lost its veneer of luxury and was generally known for the criminal activity that went on there.

Napoleon wanted to ban gambling, but was persuaded that it was a bad idea. Instead, in 1806, he passed a law that prohibited gambling except in the spa towns, which were frequented by the wealthy. He did not want the hoi polloi to gamble. This, of course, was another form of limiting gambling to only those that could afford it, but let us not think that gambling did not go on in the taverns and inns of the day. We have Napoleon to thank for gambling taxes; he imposed a specific tax on gambling.

As you can see, controlling access to gambling has been going on for hundreds of years, but for different reasons. Humans have gambled from time immemorial and various rulers and governments have tried to ban or restrict the activity without success.

Rather than introduce affordability checks, I think we need to understand more about why people are addicted to gambling (clearly some are and many are not) and offer effective treatments. Do we really think that those that are addicted to gambling will not find their way around affordability checks?

[continue reading]